Death: “Don’t grieve. Anything you lose comes round

in another form …

…

God’s joy moves from unmarked box to unmarked box,

from cell to cell. As rainwater, down into flowerbed.

As roses, up from ground.

…

Now it looks like a plate of rice and fish,

now a cliff covered with vines,

now a horse being saddled

It hides within these,

till one day it cracks them open.”

~ Rumi

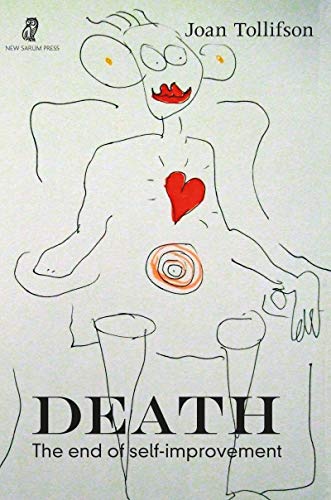

Rumi has the gift of expressing the “essence of life”…. the Mystery … and his poem, above, is the quintessential “anchoring” for Joan Tollifson’s newly released book: Death: The End of Self Improvement … and as you delve into the book this exquisite “anchoring” is revealed deeper and deeper … and, we are honored to be an “instrument of this revelation” …

When it comes to death, tip-toeing seems to be the more common experience … it is not a topic that is readily or easily invited into regular conversations. We, humans – social beings – have inexplicable behaviors: we tend to celebrate birthdays but shy away from death … despite the fact that every birthday is a year closer to death!

Turns out if we explore death it reveals insights that, if embraced, allow us to live more fully. Joan undertakes this exploration in her book that’s “… about fully embracing death, and therefore life, wholeheartedly and relaxing into the total disintegration and loss of control that growing old and falling apart— and living and loving and being awake—actually entails …”

Her book is “… not about getting control and staying young forever, nor is it about avoiding or denying any of the messiness and painful loss that aging and dying and living inevitably involve …” It is “… not a self-help book that tells you how to stay active and feel perpetually young, nor does it promise any kind of afterlife “for you” through heaven or reincarnation …”

Instead, with death as the “canvas” for her personal story (told with humor and commendable transparency) she paints an exquisite “portrait” that “… invites an awakening to the immediacy of this moment and the wonder of ordinary life …” and reveals “… a pathless path of genuine transformation, seeing all of life as sacred and worthy of devotion, and finding joy in the full range of our human experience …” …

So, in this series we offer a glimpse into this portrait … and we begin with Dissolving (the book’s opening chapter or Prologue) which is an engaging overall introduction that draws you in … so … pause … reflect … read … and continue the journey!

All italicized text (except for the block-quoted parts) is from Death: The End of Self-Improvement by Joan Tollifson and is published here with her (and the publisher New Sarum Press’) generous permission.

Here are all of Joan’s posts on Stillness Speaks … and her website – full of deeply insightful and valuable content for your journey.

During my eight years in Chicago, I went through menopause and began to experience my own aging in a new and more visceral way. Several close friends died, two went into nursing homes, all were growing noticeably older. Eventually, the year I turned sixty, I moved to Oregon. One of my Zen teachers, Joko Beck—one of the clearest, sharpest people I’d ever met—slipped into what seemed to many to be some form of dementia, behaved in strange and unexpected ways, and eventually died. My main teacher, Toni Packer, suffered a more than decade-long, painful, debilitating illness culminating in death. My first lover from college died. I got cancer. I turned seventy. On a global scale, there was talk of the sixth mass extinction being underway, and humanity itself seemed to be flirting with death in the form of climate change or nuclear holocaust. And so, rather naturally, I found myself writing about aging and dying, that time of life when everything falls apart. Paradoxically, I found that what I was really writing about was living—being alive now.

I also began to notice that aging and dying share much in common with spiritual awakening. Both involve a dissolving of old identities, the disappearance of future time, the end of the known, and letting go of absolutely everything. Aging and dying, like awakening, are a great stripping process, a process of subtraction. Everything we have identified with gradually disintegrates—our bodies, cognitive skills, memory, ability to function independently. Eventually, everything perceivable and conceivable disappears.

Am I saying that nothing survives death? Actually, I’m suggesting that there are no separate and persisting “things” to begin with, either to be born or to die. All apparent forms—people, tables, chairs, atoms, quarks, planets, dogs, cats, consciousness, energy—are mental concepts reified and abstracted out of a seamless and boundless actuality that does not begin or end, for it is ever-present Here-Now. And whatever this boundless actuality is, it seems to have infinite viewpoints from which it can be seen, and infinite layers of density, from the most apparently solid to the most ephemeral and subtle. Ultimately, there is no way to say what this indivisible wholeness is. No label, concept or formulation—whether scientific or metaphysical—can capture the living actuality.

No one knows for sure what happens after death, and I may be surprised; but I assume that dying will be just like going to sleep or going under anesthesia. Conscious experiencing—my movie of waking life and the experience of being present—will vanish as it does every night in deep sleep or under anesthesia. And, as in deep sleep, I won’t be there to miss myself or my movie of waking life. The fear of dying only exists during waking life, and only as a fearful idea. In deep sleep, the problem—and the one who seems to have it—no longer exist.

The more closely we explore this whole compelling appearance that I call the movie of waking life, the more we find that it has no more substance or enduring reality than a passing dream. We might think of it as a play of the universe, a dance of consciousness, a marvelous and deep entertainment, with no meaning or purpose except to play, to dance, to enjoy and explore and express itself, and then, to dissolve— back into that unfathomable mystery prior to consciousness, subtler than space, in which nothing perceivable or conceivable remains.

In my view, what happens after death is a flat earth question. Worrying about what happens to us when we die is like worrying about what happens to us if we fall off the edge of the earth. People used to worry about that, but their fear was based on a misunderstanding. Just as there is no edge to the earth, there is no actual boundary, no edge where life begins or ends. The things we are worrying about are all conceptual abstractions, artificially pulled out of the whole. Like the lines on a map dividing up the whole earth, birth and death are artificial dividing lines on an indivisible reality.

Just as no wave is ever really fixed in any permanent form or separate from the ocean, no person is ever actually a fixed or solid “thing” separate from the totality. This unbroken wholeness or unicity is ever-present as the still-point of Here-Now, and ever-changing as the thorough-going flux and impermanence of experience. This wholeness cannot be found or lost because it is all there is, and there is nothing and nowhere that is not it. Nothing stands apart from it to “get it” or “lose it,” and it never departs from itself. Stillness and movement, immutability and impermanence, mind and matter, are simply different ways of seeing and describing this indivisible actuality.

Of course, there’s no denying the everyday reality of death. Every living being is a unique and precious expression of the universe, a unique point of view, a unique and unrepeatable pattern of energy. When someone we love dies, they are gone, never to return, and one day, this life we are experiencing right now will end. In so many ways, death is the greatest wake-up call there is.

Someone sent me a wonderful cartoon for my sixty fifth birthday. It pictured a long line of cute penguin-like creatures waddling in single file across a vast plain that extended as far back as the eye could see, and at the front of the line, the creatures have arrived at the edge of a cliff, a very steep precipice—and the captions reads, “Man, I guess it really was about the journey and not the destination.”

When the future disappears, we are brought home to the immediacy that we may have avoided all our lives—the vibrant aliveness Here-Now, the only place where we ever actually are. Whether it is the personal death that awaits each of us, or the inevitable planetary death in which the earth itself will be no more, or even the end of the entire known universe, death is the single reality that most clearly informs us that the future is a fantasy and that the person and the world and everything that we have been so concerned about are all fleeting bubbles in a stream.

When we believe that a single, fragile, vulnerable, impermanent bubble is all we are, we live in fear of death. And yet, paradoxically, at the same time, we long to pop the bubble of apparent encapsulation and limitation and dissolve into the vast, unlimited wholeness that we seem to have lost, the no-thing-ness where all our problems and concerns vanish into thin air.

We all know, intuitively, that this bubble is not all we are, nor are we some kind of lost soul trapped inside it. The wholeness we long for is actually all there is. The bubble has never been a solid, separate, independent, unchanging thing. By embracing the actuality of life just as it is, something shifts. And surprisingly, the more closely we tune into the bare actuality, the less substantial it seems, and the more mysterious, unresolvable and extraordinary it reveals itself to be. Pain, whether physical or emotional, becomes more interesting and less frightening, and even if fear arises, that too becomes interesting rather than fearful. Everything reveals the jewel in ever-new ways.

We often have the idea that dignity means being in control, not being overwhelmed by emotion, not screaming or crying in pain, not losing control of our bowels, not vomiting on ourselves or peeing in our pants, not losing our minds, and so on. Most of us are conditioned to feel that bodily functions and emotions are a bit dirty or unspiritual and best hidden away. At the very least, they must be controlled.

As we age, and for some people much sooner in the wake of an illness or a disability, all this begins to crumble away.

We may start having falls or losing our cognitive skills. We may not be able to function independently anymore. We may need help, sometimes with very intimate tasks. We may lose bowel control, perhaps in a crowded restaurant while eating Sunday brunch with a large group of friends—that happened to my mother in her last year of life. If you’ve been with people who are dying, you know that there are usually body fluids involved and all sorts of messy things that don’t fit our limited and unreal picture of dignity. We may end up in bed, in a nursing home, in restraints, in terror, screaming—this happened to a friend’s father. I have an ostomy bag now, following an anal cancer, and I’ve had some pretty messy moments while managing the bag one-handed—I lost my right hand before birth. Are all these events undignified? Are they humiliating? Or are they simply part of life?

This book is not about getting control and staying young forever, nor is it about avoiding or denying any of the messiness and painful loss that aging and dying and living inevitably involve. This is not a self-help book that tells you how to stay active and feel perpetually young, nor does it promise any kind of afterlife “for you” through heaven or reincarnation. Rather, this book is about fully embracing death, and therefore life, wholeheartedly and relaxing into the total disintegration and loss of control that growing old and falling apart— and living and loving and being awake—actually entails.

~ Joan Tollifson

Stay tuned for more on Dissolving … in the next part … which will also include some sampling of the chapters …

All italicized text above (except for the block-quoted parts) is from Death: The End of Self-Improvement by Joan Tollifson and is published here with her (and the publisher New Sarum Press’) generous permission.

Wholeheartedly enjoyed Joans perspective and candor.

One thing stood out that I feel needs a deeper look into and it was her statement about liking death to not being aware of deep sleep. Although there’s no way of knowing what death is like there is knowing the deep sleep state, it’s just not known by the mind.