relationship : “… The most important thing is coming back to presence every day, back to the breath, to sitting, walking, and standing, and remembering that this is what we are …” ~ Norman Fischer

“… When you love someone, you have to offer that person the best you have. The best thing we can offer another person is our true presence …” ~ Thich Nhat Hanh

The way is long – let us go together;

the way is difficult – let us help each other;

the way is joyful – let us share it;

the way is ours alone – let us go in love;

the way grows before us – let us beginThis Zen invocation reminds us that the “Zen way” is all about “doing” or “being” or “living” … “us” … which is yet another way of expressing one of Norman Fischer’s four themes on Zen: “… dharma is all about … and maybe you could even say … only about relationship …” which …

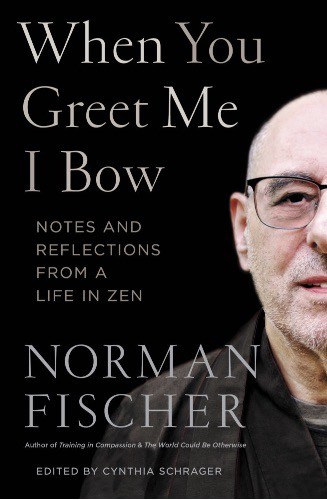

… we began exploring in the previous post of this series (part 2 of previewing Norman’s book When You Greet Me I Bow: Notes and Reflections from a Life in Zen, published May 2021) … and he underscores this theme in the final paragraph of his Introduction (Notes On The Joy And Catastrophe of Relationship) for PART ONE: A Buddha And A Buddha that’s focused on the relationship theme:

“… I am these days literally praying that when this pandemic is over (and I hope it is by the time this book is in your hands) our world will be overcome with a moral imperative to take care of one another, ensuring that no human being will have to needlessly suffer for want of food, housing, education, or medical care. Compassion—feeling the suffering of others and caring for their spiritual and physical well-being—is surely the heart of all religious teaching …”

This post offers the remaining – concluding – excerpts from the chapter When You Greet Me I Bow where Norman begins unpacking this main thesis of “Zen is all about relationship” where, notably, relationship has a broader meaning as outlined in the contextual remarks of the previous post in this series …

This is the 3rd & concluding post on Norman’s book preview based on excerpts … and is part of our recently launched Shambhala Publications series (that offers substantive previews of selections from Shambhala Publications new and classic titles) … that started with Norman’s book.

All italicized text below is adapted from When You Greet Me I Bow: Notes and Reflections from a Life in Zen by Norman Fischer, edited by Cynthia Schrager © 2021 by Norman Fischer. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO. Shambhala Publications has also generously offered a free downloadable PDF of the Table of Contents (link is at the bottom of the post).

You can purchase the book at Shambhala Publications or Amazon.

Relationship: When You Greet Me I Bow – Concluding Excerpts

“… Living together for a long time with practice as a backdrop, we can get over our need for others to be as we wish they were, and appreciate them as they are …”

Recently, I attended a funeral at the San Francisco Zen Center for the priest Shuun Mitsuzen, Lou Hartman, who had died at the age of ninety-five. He had been married for sixty-three years to Zenkei Blanche Hartman, who was coabbot of the center with me more than twenty years ago. To open the ceremony, as is the Zen custom, Blanche carried Lou’s ashes into the Buddha hall and placed them on the altar. Though there are probably very few people who appreciate the Buddhist teaching of impermanence as much as Blanche does, she cried quite a bit as she placed the ashes down. So did I.

Lou had been quite famous around the Zen center as a talker, curmudgeon, and great doubter. He was absolutely faithful to daily meditation and ritual practice and he took care of altars and small repairs constantly, but he was outspoken in his scorn for any sort of falseness or cant, was almost incapable of taking anything on faith alone, and didn’t have a pious bone in his body. His manner was gruff and probably a little scary to new students, and in some ways, despite his long marriage, fatherhood, and many years living communally in the temple, he was a loner. So the expressions of love and tender regard for him that were made at the funeral were eloquent testimony that what counts in human interaction isn’t outward sweetness, polite solicitude, or fulfilling others’ needs and expectations. It’s the capacity to show up intimately and honestly, with one’s whole self, for and with each other, over time. It’s not necessary that the people we love be perfect or even overcome what might be serious personal defects. Living together for a long time with practice as a backdrop, we can get over our need for others to be as we wish they were, and appreciate them as they are.

The celibate monks of old China and the married priests of San Francisco Zen Center may be living in unusual situations, but the basic template of what they have learned from the Zen tradition about relationships is useful for the rest of us. Though we may not be able to replicate their lives, we can, I am quite sure, find a way to capture the essence of the practice that they’ve done, and it can help us with our contemporary relationship problems. There is, of course, some serious effort involved—meditating on one’s own and at group retreats, listening to teachings, and the daily effort of paying attention. But these are efforts that can realistically and successfully be made, if you feel it’s a priority.

The most important thing is coming back to presence every day, back to the breath, to sitting, walking, and standing, and remembering that this is what we are. It’s a practice we can do with as much integrity as Guishan, Longtan, or Lou Hartman. We can remind ourselves that when our passions are aroused, or when we feel our needs are unmet, we can return to presence and just feel whatever we feel, with some forbearance. We don’t need to make it go away and we don’t need to insist that others do what we think we need them to do.

Of course, we can’t expect our lives to go as smoothly as those of the ancient Chinese Zen masters whose stories I have used here (and remember, these are stories, yarns, not memoirs). Real-life relationships will involve negotiation, push and pull, and, some- times, a necessary parting of the ways. But it makes a difference if all of this is done with some deeper basis, some deeper knowing and appreciation of one another, rather than simply needs and wants.

I have found over the years that when a couple practices together, there’s a basis or grounding for their relationship. Even if there are tough times, somehow the return to basic human presence—their own and that of others—brings them back to appreciation and affection.

In relationship, as in spiritual practice, commitment is crucial. In both Zen and marriage there’s the practice of vowing, intentionally taking on a path, even if we know we won’t get to the destination. Vowing is liberation from whim and weakness. It creates possibilities that would not occur otherwise, because when you are willing to stick to something, come what may, even if from time to time you don’t feel like sticking to it, a magic arises, and you find yourself feeling and doing noble things you did not know you were capable of.

Real love can include desire, of course, and desire is touchy and powerful—it can even capsize the boat of a great Zen master! But desire is not the only thing, nor need it define or limit our love. Insofar as loving another is being there for that person, come what may, we always have to go beyond self-interest and desire, though, paradoxically, love itself, as ultimate selflessness, may be the most personally satisfying experience possible. On the whole, when people get together in intimate relationships with some serious spiritual practice as a common basis, their chances for success as a couple are maximized, and, as with Blanche and Lou Hartman, that success can deepen and be enriched with time.

In our story, Tianhuang says, “When you greet me I bow.” Bowing is an ancient form for showing reverence and respect. In our culture we have the handshake. Maybe it is more intimate than a bow because we touch one another, warm hand to warm hand. But they say that the origin of the handshake is suspicion and wariness. The handshake is a gesture of peace and harmlessness because it demonstrates that we aren’t holding a weapon in our hands. Our hands are empty of aggression and we show this by offering our hand and taking the hand of another. So the handshake is more intimate than the bow, but the intimacy is predicated on the possibility of aggression. In contrast, by bowing we are acknowledging a friendliness and respect, but also a distance. A bow expresses our love and respect, but the space between us when we bow also expresses that we understand our aloneness, and that we can never assume we understand one another. We meet in the empty space between us. A space charged with openness, silence, and mystery.

A while ago I met two middle-aged people who had recently gotten together as a couple. Each of them had had nothing but troubled relationships their whole lives through, starting in childhood, but they were hopeful this time around. Given their past conditioning, they were understandably nervous and were seeking help. They’d already ordered several books, were looking into couples therapy, and wondered what Zen relationship advice I had for them.

“Practice this every day,” I said. “Do it first thing in the morning (or, preferably, second thing, after meditating together): Sit facing each other and say to one another, ‘I am grateful today that you are in my life.’ Say the words, even if you find it difficult. If you don’t believe them, say so. Say, ‘I just said that I was grateful that you are in my life, but I don’t really feel that this morning, although I would like to feel it,’ and then try it again; if you still don’t mean it, you can say so and give up until tomorrow. Then try again the next day, preparing yourself in advance by reminding yourself that you really are lucky to be alive, to be whole and healthy, and to have someone willing to share their life with you.”

None of these things is automatic; none of them is permanent. To be alive with others—nothing could be more basic, yet there is no greater spiritual practice.

~ Norman Fischer

Next, our Shambhala Publications Series will explore David Chernikoff’s book: Life, Part Two: Seven Keys to Awakening with Purpose and Joy as You Age … so stay tuned …

All italicized text above adapted from When You Greet Me I Bow: Notes and Reflections from a Life in Zen by Norman Fischer, edited by Cynthia Schrager © 2021 by Norman Fischer. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO. And, click here for the free, downloadable PDF of the Table of Contents.

You can purchase the book at Shambhala Publications or Amazon.

Part of a balanced relationship with ourselves and others includes being aware of the needs of others … such as the Colorado communities that are dealing with devastating fires:

Go Fund Me has set up a trusted relief fund to urgently help verified fundraisers started for people affected by the Marshall and Middle Fork fires. Donate now to help someone in need recover from the wildfires.

Also, … help for COVID remains a key need too …. so here’s a GoFundMe blog post Fundraising for Coronavirus Relief: How You Can Help the Fight that offers a very comprehensive map for the COVID relief efforts including how you can help, what to give to, and lots more …

We are supporting some of these campaigns personally and also as Stillness Speaks (through donations).

— — — —

We are all facing financial challenges but IF your situation allows you to donate and help then please do so …

THANK YOU!

May you remain safe and healthy as you navigate these unsettling times across the globe.