“A koan … brings about a radical shift in experience …” ~ Henry Shukman

It’s evening. In the boatyard behind our house the tools are silent, the workers gone home for the day. … …

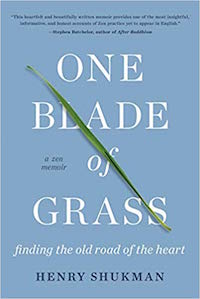

This 4-part series began with the Prologue (or part 1) from Henry Shukman’s newly released book Zen memoir: One Blade of Grass: finding the old read of the heart.

In this part 2 of the series, we share part of a chapter titled Sweet Obedience … where Henry continues with his personal stories that show the ongoing deepening of his relationship with Zen during the early part of his journey – including the ensuing doubts and questions that mark such a journey … with him recognizing the valuable role of a Zen teacher (directly experienced through his teacher at the time – John Gaynor).

It includes Henry realizing the gift of koans … how koans and an authentic koan teacher can help with navigating spontaneous awakening experiences “… integrating the experience, and living it out in an ordinary life, in kindness, in concern not for self but for others.”

So we continue our glimpse into this zen memoir … into finding the old road of the heart … so, … pause … read … reflect … and continue the journey!

And here’s … part 3 … and part 4 – the Epilogue.

It’s evening. In the boatyard behind our house the tools are silent, the workers gone home for the day. Canal boats stand at odd angles, propped on cinder blocks, their hulls burnished by grinding tools. There are oil drums, hoses, toolboxes strewn around the yard, and dustbins. Some of the boats have flower boxes on their roofs, like camper vans being serviced while still full of a family’s belongings. One has a bike on its roof.

I know this because I’ve been gazing out the window. Beyond the yard, the late sun pours through a stand of elms in a smoky stream. It’s the tail end of summer.

I’ve been making supper for my wife and myself. The boys ate earlier. I carry two plates of food upstairs. In the little bedroom, Clare lies sprawled on the bed with the boys, watching the movie Who Framed Roger Rabbit.

The room is suffused with the last of the sunlight. I bend down to give her a plate, fork balanced on the rim.

“Thank you,” she says.

I stand up straight for a moment, my own plate in hand. I’m about to sit down but get arrested by a scene in the movie where Roger Rabbit’s tail is singed on a stove, and he proceeds to accelerate faster and faster round a kitchen, trying to outrun his flaming rear, turning the kitchen cabinets into a centrifuge, like a biker on the Wall of Death.

I remember loving this scene years ago when the movie first came out. I start laughing. Something happens. A tingling, a whirring inside me. I notice how malleable the apparently solid surfaces in the cartoon are. The tingle becomes a flywheel in my belly, spinning faster and faster, until it is almost unbearable, a sweet agony. It’s in my chest now, and at once my heart just about breaks and the sensation whips itself into a cyclone, a dust devil, a whirlwind, and spins up the throat into the skull.

My head explodes. A thunderbolt hits the room. I black out—except I don’t; I’m still standing. Everything else blacks out. All the circuitry that keeps the world going snaps off. A fuse blows. I find I’m not standing on anything. Below, a chasm; above, a void; all around, in every direction, nothing. Dark, radiant nothing.

I let out a whoop and start laughing.

Clare looks up from the bed. “Oh, God,” she groans, “it’s not that Zen again.”

Stevie, five years old, looks up at me, eyes huge, clear, brown, luminous as marbles, and asks, “Daddy, what’s ‘growing old’?”

I don’t know where this question comes from—maybe he heard a line about it in the movie. I stare back into his eyes, which are alive like I’ve never seen before. Perhaps I’d never noticed. Without thinking I lean down and say, “ There is no growing old; there’s just being alive.”

We stare at each other and his face blossoms into a grin as he says, “I’m being alive.”

“Yes, you are,” I agree, and we both laugh.

I’ve been working with the koan mu ever since that first dokusan with John several months back. During a recent meeting, he told me, “I want you to start asking yourself, ‘What is mu?’”

I’ve been doing this assiduously, while riding my bike up to my office at Brookes University, while walking around town. The question “What is mu?” has started to feel like a broader question, as if it’s also asking, What is the street? The house? The bicycle? The rain?

A few weeks ago, while riding home through the drizzle, I suddenly thought to myself: Biking through the rain, getting damp: I don’t like it. But what if it’s okay, fine, it’s just what it is? Who is it saying it’s not good? For a moment I sensed that all was perfect just as it was.

And a few days ago I found myself wondering: What if there’s a mind that creates the experience of being alive, and even creates my own mind, the mind with which I apprehend things—the road, the cars, the trees? What if it’s all one mind?

Somehow what’s going on right now, with Roger Rabbit and his centrifuge, and the abyss, is connected to that question.

Yet this thunderclap is outside all calculation. There’s just empty sky in every direction. “Not one speck of cloud to mar the view,” an old Zen saying has it. Not one thought in the whole universe. Nothing exists! All this earnest training of the mind that we did in Zen—or thought we did—and there was no mind!

In the room, everything is bathed in rich light, a dark, lucent limpidity drenching the bed, the window, the TV, the three other people sprawled on it.

Giddy, dizzy, I totter downstairs with my untouched plate, delirious with joy, feeling like any moment I might topple into the abyss and not caring. How is it even possible to take a step, to be suspended on this imaginary surface called the floor? It’s all a dream, a floating illusion, a mirage-like reflection, a ghost of something on nothing.

The food looks magnificent on my plate, like a still life from a seventeenth-century master. I can’t imagine what to do except admire it. I can’t imagine what to do at all. Everything is one glorious abyss of peace that fizzes with energy.

I pull a cushion off the sofa, fold it in half, and sit down in zazen. I can’t think what else to do. At the end of twenty minutes, the carpet, sofa, and cushions are all still alive with energy.

A flicker of alarm: Am I going mad? Will this never end?

I let myself out and go for a walk around the dusky neighborhood. Billows of smoky energy seethe everywhere. The houses hang still and quiet in the gray-blue dusk. They, too, are smoky and alive, poised between being there and not being there. The mind is a wisp of smoke, the remains of a blown-out candle. Not just the houses but the seeing of the houses is the same: there and not there. I could go up and knock on their doors, tap on their windows, but “being there” isn’t what it seems. The world “out there” is a reflection quivering on nothing, even when you rap on a door.

Once again, everything answered and fulfilled.

I still can’t put into words what it was—indeed, words were one of the principal devices for screening this reality—but when you saw it, when it appeared, it folded up everyday reality like a piece of paper and dropped it in a furnace. This reality, unbearably real, loved us fiercely, it loved all things—it was like discovering that the whole world was one heart. Yet at the same time it wasn’t anything.

Later I heard John quote an old master, Dahui (“Da-way” – Japanese: Daie Soko, 1089–1163), from twelfth-century China, who said that Zen’s reality was a hot stove, and all phenomena were snowflakes that melted when they came near it.

Was that true? Was reality like that? Or was this some kind of madness? Was I being misled by John, and by Zen? But then why was I feeling so redeemed, so all right?

I had no answers. Only what I felt. Which was that, by some miraculous power, I had just been granted a glimpse into reality, into the true fabric of the universe—into its DNA, as it were, and what I had seen there implicated me too, so that it was clear that, like everything else, I was a child of the universe. I wasn’t separate from it.

Background image is from NASA, ESA – see full credit bottom of post

And all without any god. So good was this universe, intrinsically and unto itself, that no god was needed. Nothing extra at all was needed.

I was dying to see John, and went as soon as he was next available.

I told him what had happened. He diagnosed it as a “clear but not deep” experience. I was delighted. He seemed to understand every last detail of what I described, and I bowed my forehead spontaneously to the floor in a wave of gratitude such as I couldn’t remember ever feeling. I never wanted to get up. He knew. He recognized it. He understood. That was all I needed.

Then he started plying me with odd questions about the koan mu. They seemed like nonsense, yet I found responses stirring in me, and when I let them out, John would smile at my ridiculousness and agree, and tell me that I had just given one of the traditional answers. I had never known anything like this, in Zen or anywhere else. So the experience had not been random. It actually had something directly to do with mu. This was what a koan was for: to bring about a radical shift in experience. The koan could offer access to an incredible new experience of the world, free of all calculation, all understanding. But more than that, I was discovering that the koan could allow you to meet: the student could come to the teacher with their “experience” and have it met. And they themselves could be met, right in the midst of what they had awakened to.

After a number of interviews like this over the following weeks, John gave me a new koan, the famous one: “You know the sound of two hands clapping; what is the sound of one hand?” It was the best thing: a way of not just confirming and growing confident in the experience, but sharing it. It was what I had been crying out for, for decades: to meet someone in this reality. This was the magic of the koans. They didn’t just open us up; they offered a way to the most intimate kind of meeting.

But it went even further: an authentic koan teacher could lead you deeper. Only through the meeting, the sharing, the guidance was there hope of integrating the experience, and living it out in an ordinary life, in kindness, in concern not for self but for others.

~ Henry Shukman

Here’s the concluding text of Sweet Obedience (i.e., from this point onwards) or part 3 … it continues Henry’s current personal story showing the continuing, subsequent deepening of koan integration … and the continuing, ongoing value of an authentic koan teacher like John Gaynor.

And, again, here’s part 1 … and part 4 – the Epilogue.

All italicized text above (except for the block-quoted parts and the parts in braces) is from One Blade of Grass: finding the old road of the heart by Henry Shukman and is published here with his generous permission.

NOTE: Image 5a is from NASA, ESA – see full credit further below.